A relic of touch at The Walters

“I get these what I call ‘monk emergencies’ where I get this desperate phone call from downstairs at the front desk,” says Lynley Anne Herbert, Associate Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

And the person at the front desk will tell her, “I have ten Franciscans here, and they want to see the Francis Missal.”

So what Lynley ends up doing a lot of times is drop to everything, go down and get the Franciscans, take them upstairs, and pull the book out for them.

“It happens every few months, usually,” she says. “I’ve had groups of Benedictine nuns come and the brothers will come. We’ve had people from Assisi — they come from all over.” And she’s had some fun moments with them. “They’ll be in their full robes and they’ll pull out their cell phone and they’re like, ‘Can I take a selfie with the book?’ ”

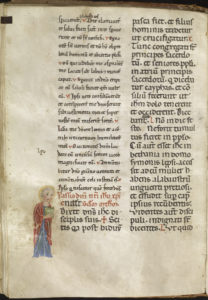

Leaf from St. Francis Missal

cc Creative Commons License

The book in question is the St. Francis Missal (W.75) dating from 1172-1228, purchased by Henry Walters in 1913 and bequeathed to the museum in 1931. The story goes that in 1208 St. Francis of Assisi was trying to decide what God wanted him to do with his life, and so he and two of his friends visited the Church of San Niccolò and randomly opened three passages of the missal on the alter:

— If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell what thou hast, and give to the poor.

— Take nothing for your journey.

— If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me.

These passages from the book on the altar became the cornerstone of the Franciscan way — and the St. Francis missal at The Walters is believed to be that book. We may never know for certain if the hands of St. Francis truly touched the missal, but it is considered by the Franciscans and others of faith to be a relic.

“This book is very important to the Franciscan community around the world,” says Lynley, “and because it is so important to them they come here assuming it will be on view. And they get to the gallery and they realize its not out, and they just totally panic because sometimes they’re coming from far away — they’ll actually make pilgrimages to see the book.”

For the past few years, Lynley hasn’t even been able to open the book for these pilgrims because it had become so fragile from wear and tear. And the visitors would say, “We don’t care, we just want to be in its presence.” Sometimes, Lynley would let them very gently touch the boards. “Because, for them, it’s a relic of touch,” she says, “so it’s more than just a book.”

The Walters Art Museum has the second best collection of rare manuscripts in the country — the first being the Morgan Library in New York.

“We have almost a thousand manuscripts at this point from all different periods and cultures,” says The Walters’ Head of Book and Paper Conservation, Abigail Quandt, whose own specialty is medieval manuscripts and the treatment of parchment.

Since the St. Francis missal is important not only in the context of the collection and exhibitions, but also gets more regular use when they have Franciscan visitors come to see the manuscript, it was recently put at the top of the priority list for conservation.

“The problem is that the binding, which dates from the 15th century, is riddled with insect holes and is in an extremely fragile condition,” says Abigail, “and so every time the book is opened, it puts stress on the binding,”

“The problem is that the binding, which dates from the 15th century, is riddled with insect holes and is in an extremely fragile condition,” says Abigail, “and so every time the book is opened, it puts stress on the binding,”

The conservation project got underway in the spring of 2017, and it promised to be lengthy, requiring a great deal of research, so it became an ideal project for an Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship, which went to Cathie Magee, a post-graduate fellow in book conservation. One early April day in 2017, I slipped in at the back door of The Walters on Mt. Vernon Place, and was taken through the warren of corridors to the light and airy book and paper conservation laboratory. The precious missal was on a high table, carefully placed in a special holder that wouldn’t further damage the spine. It’s age radiated from it in this clean, clear space, which had the aura of an operating theater.

“These are two of the book illustrations,” said Cathie, touching the missal with tender fingers.

I was surprised that she wasn’t wearing gloves.

“It’s skin,” she explained, “and so the oils from your skin aren’t really going to hurt it as long as your hands are clean.”

The Walters’ Head of Book and Paper Conservation, Abigail Quandt, and Cathie Magee, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Book Conservation

“And we should make it clear that it was a copy, not somebody just writing from memory,” said Abigail. “They’re copying another book. It was called an exemplar, a model. It could be a manuscript — say, a Gospel book — that they didn’t have so they asked a neighboring monastery to borrow a Gospel book and then they had it on ‘interlibrary loan,’ so to speak, for a certain period of time to allow them to make their own copy, and then they hopefully returned the book.”

“It’s a humble book,” said Cathie. “But it was well loved, clearly. It’s darkened, and some of it is through use and age, but we also think that some of this might be the result of cleaning.” She showed me a spot where the parchment was really rough. “Dealers would sometimes go in with a knife and actually scrape the surface of the parchment because that’s really the only way you can get off the dirt and the grime.”

The original text block is from the 12th century, but the book was rebound at some point — they don’t know why — and they believe that was done in the 15th century based on the style.

“It’s a very common 15th century Italian style,” said Cathie. “The leather on the boards we think is actually 19th century. That’s based on the tooling and also the condition — it’s just really awful. 19th century leather never looks good.”

I was very curious to know why.

“It was part of the whole industrial revolution,” said Abigail. “Everything was sped up tremendously and mechanized so that before, in medieval times, you would have an individual craftsman actually sourcing the hides, processing them in a very gentle way, using naturally available materials. Whereas with the industrial revolution, there was a lot of introduction of new techniques, which sped up the process but unfortunately left a lot of very acidic chemicals in the leather that then eventually led to its degradation.”

When it came time for the actual conservation of the missal to begin, Cathie started at the back, since it’s always a good idea to start from the back of these things — just in case. Also, the back was in worse shape so it was be easier to get it off first. She took a scalpel — my analogy of the operating theater was not far off, you see — and ran it along the place where there was not much leather. Once the backboard was off, she flipped the missal over and did the front. Then, putting it upright in a press, she removed the leather on the spine with a spatula tool. With the spine exposed, they could see all sewing supports and the extent of the adhesive that was on the spine. Because parchment is so moisture sensitive, Cathie painstakingly picked off as much of the dry adhesive as she could with a tool.

“One of the challenges I put to Cathie,” said Abigail, “was ‘what are some of the new cutting edge techniques in objects and painting conservation that maybe we could adapt for book conservation?’ ” One technique Abigail had seen that everybody was talking about was the use of gels for removing adhesives and stains, which she found exciting because it is very effective and very gentle for the art.

“I’ve been looking specifically at a substance called gellan gum,” said Cathie, “which was actually developed by the food industry.”

“It’s also in shampoos and cosmetic products,” said Abigail.

“It’s a stabilizer, basically, and you really don’t need very much at all to make a gel.”

Cathie experimented with combining two different kinds of gels to get something that was both flexible but also more rigid to remove as much of the glue as she could with as little pressure on the parchment as possible.

“Scraping is not the best for wet parchment. You can end up doing quite a lot of damage, and wet parchment in general is also really a problem. So I was able to scrape off the glue pretty easily after applying these gels. There’s a lot of variables to play with but it’s a really fun project because you get to do science and think about how the solvents I use are going to affect the object, and how I can maximize the effectiveness of my treatment.”

Once the glue was removed, Cathie started taking the missal apart, section-by-section. With the individual sections separated, she took apart the bifolia — the two sheets of parchment folded together to make four leaves — looking at the specific condition issues.

Once the glue was removed, Cathie started taking the missal apart, section-by-section. With the individual sections separated, she took apart the bifolia — the two sheets of parchment folded together to make four leaves — looking at the specific condition issues.

“I’ve got this gigantic Excel spreadsheet,” she said, “where I document if there’s a hole on this page and a stain on this page, and then address them as they need to be so the tears will be mended.” She also did photo-documentation each step of the way. “With a project of this scope, you want to document the book in stages as you move along.”

Certainly, the missal took up a lot more space when it was deconstructed, but luckily all of the folios were numbered so they could keep track. When it came time to reverse the deconstruction and sew the cleaned and mended pages back together again, the plan was to use a very strong linen thread, almost the same as the original, on a sewing frame like the ones that have been in existence since at least the 12th century.

“We have an image in a manuscript,” said Abigail, “so that’s how we set it up.”

Doing this kind of conservation work in a museum, as opposed to a library, meant that they had access to other conservators at The Walters who have different expertise from theirs. Next door to them is the objects conservation laboratory, where they are very experienced at dealing with wood, metal, lacquer, and all kinds of materials.

“It’s really fun,” says Abigail, “because books, especially old books like this, are very mixed media. One of the interesting things is — and this is where Lynley comes into the conversation as the curator — she approves of the treatment, but how do we deal with the losses on the edges of the board?”

One option was to fill the loss with something that would be strong and sturdy but would have a very different look. Another option was not to repair it but to stabilize it and accept it for what it is.

“And the question,” says Lynley, “is your treatment being irreversible versus the loss being irreversible.”

“The philosophy of modern conservation is reversibility,” says Abigail, “because we know that we’re not going to be the only ones treating these objects, and we want to be sure than anybody in the future here at the museum or in a different scenario would be able to undo what we did if they feel that’s necessary.”

And so, as they prepare to hand the St. Francis missal on to future generations, they will also be able to have it on view at The Walters again this fall and make it available to the Franciscans who continue to make pilgrimages to see it.

“It’s really about the fact that somebody holy has touched this,’ says Lynley, “and therefore they’re that close to Francis in their minds. And so it has a life of its own.”

[Photo credits: John Dean]

Tags:St. Francis Missal, The Walters Art Museum

8 Responses to A relic of touch at The Walters